Global Nation

A daily public radio broadcast program and podcast from PRX and WGBH, hosted by Marco Werman

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story was originally produced by Houston Public Media and has been updated for The World.

For the last three weeks, Houston plumber Eduardo Dolande has been working long hours to help repair burst pipes in local homes and businesses.

Just in his own Houston neighborhood of Cypress, Dolande, who has worked as a plumber for 21 years, said he's helped about a dozen families with their pipes — as a favor, free of charge. The destruction he’s seen inside some homes looks like something out of a movie, he said.

“It's just wet sheetrock everywhere, and then the insulation that was up in the attic was on the floor. ... It just looked horrible."

“It's just wet sheetrock everywhere, and then the insulation that was up in the attic was on the floor,” Dolande said, “It just looked horrible."

One of the damaged homes was his own. At one point, he ran out of supplies to fix his own pipes after using them to help his neighbors. His plumber friends eventually helped him find some replacement parts, which have been in short supply since the storm.

He had to cut open parts of his ceiling in two bathrooms and other parts of the house to reach busted pipes and repair them. Since he knew to turn off his water before the freeze, the damage in his own home was minimal — but the family still had water all over the floors while they tried to fix multiple burst pipes.

Dolande said his neighborhood was also hit hard by Hurricane Harvey, but that the freeze was worse because it took people by surprise.

“No power, no water,” Dolande said. “People get desperate over that.”

Related: Freezing temps wreak havoc on utilities in US and Mexico

“I've never seen that much damage in homes,” he said. “Never.”

In the aftermath of the storm, plumber Eduardo Dolande also had to fix the pipes in his own home.

Courtesy of the Dolande family

Texas' largest insurer, State Farm, has reported more than 44,000 claims in the state related to the winter storm. That's more than 10 times the total number of burst pipe claims they saw nationally in 2020.

And immigrant workers — like Dolande, who is from Panama — are critical to repairing that damage, according to Jeremy Robbins, director of the New American Economy think tank.

“As people are trying to build back, they're trying to repair their houses, they're trying to figure out how to survive the damage, immigrants are playing outsized roles in so many of the professions that are essential to the Texas economy,” Robbins said.

The group’s analysis of 2019 American Community Survey data found that in the city of Houston, about 40% of plumbers and 63% of construction workers are foreign-born.

In Texas, 27% of the state’s plumbers and 40% of construction workers are foreign-born, though immigrants make up about 17% of the population. And the share of immigrant workers is even higher when other labor-intensive jobs are taken into consideration.

“If you look at drywall installers or ceiling tile installers and tapers, more than 75% of them nationwide are immigrants."

“If you look at drywall installers or ceiling tile installers and tapers, more than 75% of them nationwide are immigrants," Robbins said.

Related: From 'aliens' to 'noncitizens' – a Biden word change that matters

Houston plumber Eduardo Dolande shows where pipes burst inside his own home during the Texas freeze.

Elizabeth Trovall/Houston Public Media

These workers will play a critical role as second responders, since many ceilings — like Dolande’s — have been damaged from burst pipes.

Steven Scarborough, strategic initiatives manager for the Center for Houston's Future, said without immigrants, weeks-long repair wait times would last even longer.

“Imagine all these stories you've heard, how long people [are] waiting for plumbers, and increase that by 37%,” he said.

Related: Blackouts across northern Mexico highlight country's energy dependence

Though these immigrant workers are essential to storm recovery in Houston, many come from communities that tend to be disproportionately impacted by catastrophic events.

A Rice University survey found nearly two-thirds of Hispanic immigrants in Houston could not come up with $400 to pay for an emergency expense. And those families are also less likely to reach out for aid in a crisis, Scarborough said.

Eduardo Dolande and his wife, Mitzila Guerra, became United States citizens after immigrating from Panama.

Elizabeth Trovall/Houston Public Media

Eduardo Dolande is a citizen — but many Texas plumbers and hundreds of thousands of construction workers are undocumented. And they’ve become a convenient political punching bag for Republicans in recent years.

During a press conference earlier this week, Governor Greg Abbott told Texans, “There is a crisis on the Texas border right now with the overwhelming number of people who are coming across the border.” Abbott often frames unauthorized immigration as a threat.

The governor also recently reopened the state and lifted the mask mandate — a move that confounded Jessica Diaz, who works with day laborers and other immigrant workers as legal manager for the Fe y Justicia Worker Center in Houston.

“I want to understand what his point of view is…how we came to the conclusion that this is a good idea?" she said.

Diaz said she’s concerned about lifting the mask mandate while less than 10% of the state has been fully vaccinated.

During the pandemic, her organization has received nearly 400 safety and health complaints. She said day laborers — who offer cheap, immediate repairs — put themselves in vulnerable situations to secure work.

“Whoever gets in the car the fastest is the one that’s going to get the job. You don’t even ask how much they’re going to pay you. You don’t even ask about the employer, who they are or where they’re taking you."

“Whoever gets in the car the fastest is the one that’s going to get the job. You don’t even ask how much they’re going to pay you. You don’t even ask about the employer, who they are or where they’re taking you,” Diaz said.

In the four weeks after Hurricane Harvey, the University of Illinois found that more than a quarter of day laborers had experienced wage theft.

The Fe y Justicia Worker Center is already investigating wage theft claims from workers who helped with winter storm recovery.

“This is something we have seen repeatedly since Hurricane Harvey. Houston, in general, is a city that is in constant reconstruction mode,” she said.

The pattern of disaster, recovery and abuse is all too familiar — and Diaz said she doesn’t see anything changing soon.

Eduardo Dolande, who first came to the United States as a tourist in his early 20s, and became a citizen through his wife, Mitzila Guerra, said he hopes people can see that immigrants like him — including those without legal status — are helping the city rebuild.

“We are everywhere. We are helping everybody,” Dolande said. “Whether they say they don't need us, or they don't want to accept it, it is so obvious.”

Last month President Joe Biden instructed the Department of Justice to end contract renewals with private prisons as a first step to end racial disparities and pave the way to fair sentencing.

But Biden, who ran on promises to make sweeping changes to immigration policy, left private immigration detention untouched, allowing the Department of Homeland Security to continue renewing contracts with these private facilities.

For years, immigrants in detention and advocacy groups have documented a lack of oversight and physical and mental abuse at the facilities. Today, about 80% of immigrants in detention centers are in private detention, according to an American Civil Liberties Union report.

Advocates say that ending the migrant detention system is one more piece of the puzzle in achieving racial justice and ending migrant abuse.

In 2020, 170,000 people cycled through detention, which is an unusually low number compared to other years. The pandemic, along with former President Donald Trump’s tough policies on immigration contributed to those lower numbers. Policies like the Migrant Protection Protocols, also known as “Remain in Mexico,” kept asylum-seekers on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border.

Related: Reuniting families after Trump's zero-tolerance immigration policy

Still, detention continues to be a lucrative business.

The US government used to oversee immigration detention. But that changed after 9/11 with the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Immigration detention expanded after that, and US officials turned to private prison companies to manage this work. The companies jumped right in.

“They [companies] started seeing the federal government as a place to have these more lucrative contracts,” said Silky Shah, executive director of the Detention Watch Network, an immigration detention advocacy group.

The group has tracked the increasing privatization of the detention system during the Trump administration, with more multimillion-dollar contracts signed by key companies such as CoreCivic Inc and GEO Group.

Related: The winding journey to reunite families separated at the US border

During the pandemic, many immigration detention centers have also become COVID-19 hot spots. These private companies say they take safety seriously, especially during the pandemic. Immigrants are given face masks and medical attention, they say.

But addressing abuse and neglect is only the beginning of a much larger detention problem, Shah said.

It’s also about racial justice.

“What we know about these systems [is] that [they] disproportionately target people of color and Black people, and we're seeing that even now, in the context of who is currently in detention and who is being deported."

“What we know about these systems [is] that [they] disproportionately target people of color and Black people, and we're seeing that even now, in the context of who is currently in detention and who is being deported,” she said.

Biden said he wants to address racial inequity inside detention centers, too.

But unwinding these contracts might be more of a battle. Last August, the Trump administration renewed contracts with GEO Group and CoreCivic, Inc., in Texas, to run two facilities for an additional 10 years.

Any steps Biden takes now need clear deadlines to phase out these and other private contracts, said Jesse Franzblau, a policy analyst with the National Immigrant Justice Center, which provides direct legal services to immigrants.

Franzblau said giving these companies a two-year deadline is reasonable, and the federal government has the authority to do so.

“But they need direction from above to start carrying that out,” he said.

Advocates also stress the fact that nearly one-third of immigrants held in detention centers don’t have a criminal record. And many others have minor nonviolent offenses.

Shah points to other options.

“There are models that include GPS monitoring that are just alternative forms of detention. And so, I think the alternatives that do work are, one, people should just be with their families,” she said.

GPS monitoring involves ankle bracelets to track people while their immigration cases go through the courts. States like California and Florida do this more than other states, although the practice has also come under scrutiny.

Shah said it’s possible that Biden could be holding back on dealing with immigration detention as a way to leverage his other immigration goals.

But with Alejandro Mayorkas’ recent appointment to secretary of Homeland Security, along with Biden’s recent executive orders addressing deportations and travel bans, Shah said there could be some shifts in how the agency operates around detention.

Still, advocates like Shah and Franzblau say ending contracts with private detention centers is only a fractional part of a larger, problematic system. There are other aspects to address — like county jails. An executive order phasing out private contracts might not apply to county jails that also contract with the federal government to detain immigrants.

Johannes Favi is an immigration rights activist.

Courtesy of Johannes Favi

“It’s just horrible to live in detention, you know, you just want to give up on everything."

“It’s just horrible to live in detention, you know, you just want to give up on everything,” he said.

Favi overstayed a 2013 visitor visa and was in the process of applying for a green card, which his wife, a US citizen, sponsored. During a court hearing for a previous financial crime he pled guilty to, immigration officials arrested him.

He spent 10 months in a county jail, 60 miles south of Chicago. He was released in 2020, right as the coronavirus pandemic began to spread inside that facility.

Favi is now living in Indianapolis, Indiana, and continues to advocate for detained immigrants.

For him, detention — privatized or not — is the same.

“So, I really wish the Biden administration can break the whole system down, you know, detention for profit, you know, private detention, county jail.”

For now, immigrants like Favi and those working to dismantle the detention system altogether will wait to see how — and when — Biden might change it.

It was a rare rainy morning in National City, California, just a few miles north of the border between the United States and Mexico.

Nora Vargas, a Planned Parenthood executive and community college board member, was going door-to-door trying to do something no Latina had done before — win a seat on the powerful San Diego County Board of Supervisors.

Related: What impact will Latino voters have on North Carolina in the future?

For over two decades, the five-person board has been filled exclusively by white people, and, until just recently, was entirely Republican in a county that’s begun to swing hard toward Democrats.

“Happy Sunday from National City!” Vargas said to her phone, from underneath a rain jacket. “It’s actually raining a lot, but we’re here to knock on doors.”

Her board district is overwhelmingly Latino and filled with immigrants. But demographics aren’t destiny — and Vargas squared off against seven other candidates, including the area’s state senator. She had to work for every vote.

“Folks in the community would say, ‘We’re going to give you a chance, but we’re going to be watching you. Because politicians come here, they ask us for things, but they never come back.’ That’s the piece that’s really important. We have to deliver for our communities.”

“Folks in the community would say, ‘We’re going to give you a chance, but we’re going to be watching you. Because politicians come here, they ask us for things, but they never come back.’ That’s the piece that’s really important. We have to deliver for our communities,” Vargas said.

Vargas squeaked into the top-two general election by a margin of 800 votes. Eight months after that, she won a commanding victory — becoming the first immigrant, the first Latina, and the first Democrat to represent her district.

Related: This young Latina calls health insurance ‘life-changing.’ She hopes Biden will help everyone get it.

Now, a month after taking office, Vargas is the vice chair of the San Diego County Board of Supervisors, constantly shuffling between press conferences regarding the coronavirus vaccine rollout, and lengthy meetings trying to appropriate federal relief funds. It’s exhausting, but even deep into the evening, she’s still radiating energy as she speaks about it.

“I still wake up every morning thinking, ‘Wow, I get to be a supervisor,” she said.

Vargas was born in Tijuana. Her mother was a US citizen, and her father was a Mexican citizen, something that’s pretty common in the cross-border megalopolis of San Diego and Tijuana.

Going back and forth between two nations is where she believes her political journey began.

“I think when I realized that I was in a very unique state because I was able to cross the border, that’s when it hit me,” she said. “[I thought] ‘What can I do to make the world better for other people, who don’t have the life experience and privilege I have?’ I think that politics was an avenue for me to do that.”

For Latinas in San Diego, there wasn’t much of a roadmap to political power. Local political offices were handed out by powerful party machines, not leaving much of a path for young people looking to get involved in politics.

So, Vargas had to look elsewhere.

Related: Latino teen hopes the Republican Party can reform itself

“To be a Mexicana, a Latina, and then later on, what my friends would say, an honorary Chicana, I really count my blessings where going away for college was encouraged. I needed to see the world. I needed to learn,” Vargas said.

Watching her own mother work in local nonprofits, and her grandmother run a cross-border business, she realized that they were “unintentional feminists.” She brought their perspectives to a Jesuit university in San Francisco, where people with far more wealth and far less diverse life experiences were trying to figure out what was best for immigrant and low-income communities.

“Having those conversations about what feminism was and what women’s rights were had me trying to figure out what does that mean to communities of color, for people who don’t have access or opportunities.”

“Having those conversations about what feminism was and what women’s rights were had me trying to figure out what does that mean to communities of color, for people who don’t have access or opportunities,” she said.

Vargas found a place to organize and center her work at Planned Parenthood where she eventually became an executive.

“I was a patient at Planned Parenthood, and in my household, no one talked about sex or sexuality or reproductive health care,” she said. “There’s a lot of myths, and in the Latino community, there’s a taboo about speaking about sexuality. It was eye-opening for me that these services were available for young women.”

Access to health care was a fundamental part of Vargas’ campaign. The county’s board of supervisors has the power to build new hospitals, curb pollution and direct millions of dollars to better health outcomes.

But in San Diego, for decades, that board has not reflected the diversity of the border region.

“Particularly since the ’90s, the board definitely had a complexion,” explained University of San Diego politics professor Carl Luna. “It was white and Republican. There was gender diversity, but that was it.”

Related: After 2020 election, first-time Latino voter worries about a divided US

In many places in the country, local governments like a city council or town board would hold considerable power over local spending. But in California, the county board of supervisors holds the money bags. And the San Diego County Board of Supervisors is sitting on a vast amount of funding from state and local taxes.

“Seldom anywhere in America do five people have so much power,” Luna said.

In the recent past, the San Diego County Board of Supervisors’ Republican majority has built up a huge reserve of funds, adhering to more conservative values of government. While not entirely in step with all the priorities of the Trump administration (especially when it came to the environment), the board voted in early 2018 to support the Trump administration’s lawsuit against the state of California’s “sanctuary policies” for immigrants.

That began to change in November 2018, when the first Democrat in decades, Nathan Fletcher, won a seat on the board. He pushed the other supervisors in a more progressive direction, including funding a shelter for asylum-seekers who had just crossed the border.

But Fletcher, now the board’s chairman, recognizes that the board needs to lean heavier on Vargas than on some other members, given the diversity of life experience she brings to the board. The rest of the board remains white.

Vargas was immediately put in charge of the county’s vaccine distribution efforts to the Latino community.

“Nora Vargas, the burden she faces is she has to work harder to give voice and perspective to the community she represents. Because that community has never had representation at the same level.”

“Nora Vargas, the burden she faces is she has to work harder to give voice and perspective to the community she represents. Because that community has never had representation at the same level,” Fletcher said.

Vargas believes that reaching the community in ways they’ll not only understand but also trust, is the key to ending the pandemic in Latino border communities, which have been devastated by COVID-19.

“I’m talking and I can just code-switch like that,” Vargas explained, switching into Spanish. “And I did it today, and we were talking about environmental justice and I switched because language shouldn’t be a barrier. After the press conference, I started getting texts from people saying like, ‘Thank you for doing that,’ and that it meant the world to them. But it’s who I am, it’s my community and I want them to understand that they’re being heard.”

Latinas, in particular, are leading the way into political office in the state and the country, says Dr. Inez González, who runs MANA De San Diego, a national organization helping Latinas get involved in public service.

“People want to make a difference, but people need to know where the power is,” said González. "There’s certain boards, like the water district board, that people don’t pay attention to.”

Right now, in the same district that Vargas represents, Latinas are the mayors of National City and Chula Vista. But important positions all over the county are up for grabs if there’s a structure for Latinas to succeed.

MANA De San Diego pushed Vargas to join her first nonprofit board, and they want young Latinas, who turned out in November’s election, to start running for office now — and not wait for seats to open up.

For Vargas, that’s the most important part of her journey. She’s hired several young community organizers to work for her.

“I really want to make sure it’s not as hard as it was for me. My commitment is to try to make sure that the system is really shaken so that the opportunities are there for women and communities of color to rise,” Vargas said.

She hopes that after her, San Diego County politics will never be the same.

Editor's note: This article was produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

Like many therapists, Lu Rocha uses breathing techniques, meditation and yoga in her practice, but she also asks clients about their personal beliefs: “What stories have you heard about in your own family, your own community, what did they do for healing?”

Some tell her that they pray with a rosary. Others, from parts of Latin America, say their grandmothers used to rub an egg on their bodies to ease headaches. They believe the egg absorbs negative energy. Rocha gets it — her parents are from Mexico. She also gets what many of her clients have faced — years of the Trump administration’s tough immigration policies.

"...[T]hese past four years is trauma just about every week. And my people are tired, my people are sick, my people are dying.”

“When I was 5 or 6 years old, I walked around with my birth certificate because raids always happened and pickups with the immigration always happened,” said Rocha, who lives in Chicago. “But this is different this time; these past four years is trauma just about every week. And my people are tired, my people are sick, my people are dying.”

Rocha is a member of the Latinx Therapists Action Network, which now has a presence in 20 US states. To take part, therapists must be committed to supporting immigrant communities and the movements allied with them.

Deportations, family separation and detention have long taken a toll on the mental health of many immigrants in the US, along with the advocates who defend them. But the pandemic and uncertainty about immigration policies have magnified inequalities that were already present for marginalized communities, compounding their trauma.

Related: The pain of family separations is still being felt. What could Biden do?

Rocha has seen this firsthand over the past four years but especially leading up to the 2020 presidential election.

“I had DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] recipients and we were creating safety plans,” said Rocha who specializes in trauma, serving communities of color and immigrants.

She also had pregnant clients who were undocumented and fearful that if they were to get deported, there wouldn’t be anyone to care for their children.

Related: Challenges await the distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine

“This is the reality for my people,” Rocha said.

Therapy can be too expensive for uninsured undocumented immigrants — that’s why some of the therapists in the nationwide network offer sliding-scale fees regardless of immigration status. Historically, these services are not easy to come by for uninsured patients, and especially for those who are undocumented immigrants with very limited options.

Before the pandemic, 93% of Latinos who suffered from mental illness or substance abuse were not getting treatment, according to the latest survey from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Francisca Porchas is the founder of the Latinx Therapist Action Network. Her work was inspired by the experiences of activists advocating in immigrant communities and the emotional toll that it took on them.

Courtesy of Puente

Francisca Porchas, a longtime immigration rights activist, created the therapists’ network in 2019. Porchas’ fight against deportation and immigration detention with groups like the Puente movement in Phoenix exposed her to a lot of trauma, and she realized that suffering affected activists, too. But there weren’t any healing support networks.

“I'm an organizer. I know how to bring people together,” she said about her idea. “And so I want to bring healers, therapists, different types of folks together to really support and bring the kind of resources to the community that's needed,” she said.

Over two years, Porchas got 84 therapists to join the network. It took time to find therapists who are, in some cases, immigrants themselves and might understand what it is like for someone to experience deportation.

Related: Addressing mental health toll of hurricanes in Honduras

For Porchas, healing is political and when therapists stand up against homophobia, racism and discrimination, it makes a difference. Without that understanding, there’s a risk that someone who needs help might give up. That almost happened to Rey Wences, 29, a human rights organizer in Chicago. Wences didn’t feel understood by therapists in the past. “I had to do a lot of background explaining the context of immigration law. Spending that time talking about immigration policy and just like demystifying some of the misconceptions that this therapist had,” Wences said.

Listen to a version of this story in Spanish here.

Wences heard about the Latinx Therapists Action Network through Porchas and found a therapist who stuck because of shared values.

Related: Mental health concerns for students of color heightened amid pandemic

The network is also working to expand its reach online through workshops. Recently, they held a Facebook Live event with therapist Brenda Gándara, hoping to connect with Spanish speakers. Gándara spoke about anxiety and provided grounding techniques to some of the participants. A few wrote in the comments section online that they had experienced anxiety and stress, and others asked for techniques to help teenagers facing it. Over 500 people have viewed the Facebook session.

This past summer, the therapists got a request from Siembra, an immigrant rights group in North Carolina, that said its community was overwhelmed with grief, fueled by the pandemic, job losses, evictions and anxiety about immigration enforcement.

Sandra, 40, who had to quit her restaurant job to care for her children now at home for school, connected with the network through a workshop organized for Siembra. Sandra, originally from Mexico, asked to use her first name only because she’s undocumented.

“If I go to the store and the police pull me over and I get deported? And I’m jobless. So many things, the stress became unbearable."

“If I go to the store and the police pull me over and I get deported? And I’m jobless. So many things, the stress became unbearable,” she said in an interview in Spanish.

Related: Stockholm's mental health ambulance could help the US rethink policing

Sandra got depressed when the pandemic started, and she felt anger toward her four children. Because she lives in a rural area, she couldn’t find a Spanish-speaking therapist who understood her culture and circumstances.

Through the Latinx network, she attended a workshop and learned breathing techniques. A therapist also described her anxiety in a manner no one had before, using words she understood. She was also reminded of more traditional ways to heal, like connecting with her ancestors. Sandra liked that suggestion. Now, every few weeks, she pours herself a cup of tea, and talks to her deceased grandmother and mom, as if they were at the table with her.

“With that cup of tea, I can have long conversations with them, even if they’re not here,” she said. They still exist in her mind and they’ll never leave her, she said. “They are my respite, my connection and my peace,” she said.

This story is part of "Every 30 Seconds," a collaborative public media reporting project tracing the young Latino electorate leading up to the 2020 presidential election and beyond.

Growing numbers of Latinos in Georgia have come out to support the Black Lives Matter movement over the past few months — and increasingly, it’s shaping how they could vote in the upcoming US general election.

Jerry Gonzalez, the executive director of the Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials, recently took part in a recent Black Lives Matter protest in Atlanta. GALEO is focused on getting Latinos in Georgia to the polls.

“Police killing unarmed Black and brown people is really something that has not been addressed systemically,” he said at the protest. “And Latinos stand in solidarity with the African American community in making sure that justice is served.”

Racial justice and police brutality are also important to 20-year-old Leticia Arcila, a first-generation, Mexican American who will vote in her first presidential election this November.

“It's just so frustrating to see how many people have to die and have to face fear every day in order for you to understand that this is wrong,” she said. “It's just so hard to wrap my mind around that some people truly don't believe that Black lives matter.”

Related: For this young Latina voter, pandemic highlights need for 'Medicare for All'

The Latino vote could be pivotal in this election and could help turn some red states blue — or at least more purple. Most Latinos in the US tend to vote for Democratic candidates, but around a third voted for Trump in 2016. As a bloc, their votes — and the issues they care about — could be influential, particularly in a close election.

In Georgia, a battleground state, there are more eligible Latino voters than there were in the 2016 midterm election. And in 2016, Donald Trump won Georgia by just over 211,000 votes; now, there are more than 240,000 Latinos registered to vote in the state.

On Friday, Trump visited Atlanta, where he appealed to Black voters by unveiling his plan for Black economic empowerment and expressing his support for making Juneteenth a federal holiday. The president also spoke about police brutality and the recent deaths of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery at the hands of police — though he said the Black Lives Matter movement is hurting the Black community.

He did not address Georgia’s Latino community, though he also recently made a campaign stop in Florida to appeal to Latino voters there.

Related: How Puerto Ricans in central Florida may decide the US election

Arcila, for her part, said she doesn't like the way US officials nationally and locally have handled the coronavirus pandemic. She's watched how other countries have approached it and seemed to be containing the coronavirus more effectively.

That’s influencing how she votes, too.

“Other countries are getting their things together and they're actually taking care of their people and they're looking out for their citizens,” she said. “And I'm over here struggling, working a cashier job, risking my health and my family's health because I have to pay my car, because I have to pay my school, because I have to help my mom with rent.”

This story is part of "Every 30 Seconds," a collaborative public media reporting project tracing the young Latino electorate leading up to the 2020 presidential election and beyond.

By her first day of college last week, Marlene Herrera had moved several times since the coronavirus pandemic hit.

First, her mother, three aunts and cousins all moved into one house to save money. Now, Herrera, who is 18, splits her time between that house, her father’s house and another house with an aunt. She's helping take care of three younger cousins while also taking classes on Zoom.

Amid the shuffle, Herrera didn’t know whether she’d been counted in this year’s census. Her mother said she had been — as one of 13 people in her aunt’s household. Though Herrera will vote in her first presidential election this November, not all of her family members will be eligible to do so, given their varying immigration statuses. But being counted in the census ensures they’ll play a small part in the US political process.

Herrera’s housing situation is typical for US families whose finances have fluctuated during the pandemic. Like hundreds of thousands of workers across the country, her mother was briefly laid off and faced delays before her unemployment insurance kicked in. Those income gaps have led families to double and triple up to keep a roof over their heads.

Marlene Herrera, 18, will vote in her first presidential election this November.

Adriana Heldiz/The World

The instability is one reason census organizers are worried about a possible undercount among Latino communities. A Brookings survey from late July found that 29% of Latino families have had someone in their household lose their job during COVID-19, and that 49% of Latino renters are having trouble paying their rent. Latinos, especially young Latinos, have already been undercounted in previous censuses. Past undercounts have led to less federal funding for predominantly Latino neighborhoods and less representation in Congress.

Another worry for Latino advocates and census workers is that they’re running out of time to find and count everyone.

Related: 'COVID-19 is in charge of the census,' says former US Census Bureau director

After initially extending the census deadline to the end of October, the Trump administration announced last month that in-person counting efforts would end Sept. 30. The Census Bureau said it will end door-knocking operations in the San Diego area and other parts of the country on Sept. 18.

Some Latino organizers say getting Latinos counted in the census can bring about even more change than casting a single vote. While elections take place once or twice a year, getting counted in the census means one person’s existence will be used again and again to provide funding to their community for the next decade. The census counts people regardless of their immigration status.

The CARES Act, the pandemic relief funding bill Congress passed in March — was allocated in part based on the 2010 census.

Paola Aracely Ilescas, a community health specialist, organizes agricultural workers from Mexico and Central America who work in avocado fields in northeast San Diego County. Most of them can’t vote because they are not US citizens: They're either legal permanent residents, undocumented or work on temporary visas. Their children, many of whom are US citizens, are still too young to vote.

So for the workers to participate politically, Ilescas wants them to get counted in the census.

“We tell them, 'You count yourself this year, you’re making sure you count for the next ten years'.”

“We tell them, 'You count yourself this year, you’re making sure you count for the next ten years',” said Aracely Ilescas, who works for Vista Community Clinic, a nonprofit health center. “You don’t count yourself this year, you basically are not receiving or don’t exist for the next ten years. And guess what? We’re going to lose $2,000 each year for each person that doesn’t count for the next ten years.”

But Aracely Ilescas says it’s hard to get a community that’s been relentlessly targeted by immigration enforcement to answer questions from government workers who are now knocking on doors tracking down people who haven’t yet answered the census.

“Many of them have said other people have expressed distrust,” she said. “Are they really employees or are they faking to be employees in order to get them? Because for years we’ve been saying, ‘Don’t open the door to ICE officials. This is your right.’ Now we’re saying, ‘Open the door!’”

That transition, she explains, requires trust between organizers pushing for an accurate census count and local communities. But in California, where 27% of the population is immigrants, other issues — such as wildfires and the pandemic — are taking priority.

Related: Pandemic, privacy rules add to worries over 2020 census accuracy

On a recent sweltering day in San Marcos, an inland city in southern California, wildfires threatened rural communities. Arcela Nunez-Alvarez, a community organizer, had planned to lead volunteers to pass out census literature. Instead, they helped with relief efforts when the fires reached area farmworkers.

Nunez-Alvarez trains workers to become community leaders.

“We work with a lot of adults, many have very limited formal education. They’ve had to work their entire lives, but care about their community,” Nunez-Alvarez said, standing outside of a low-income housing development beside a box of signs reminding people to fill out the census. She grew up in the area and understands the importance of messaging: it needs to come from someone they trust.

“These leaders live in apartment complexes like this one here, around us,” she said. “They’re members of the community, they speak the language of the community, they look like the community that we’re trying to reach.”

While many community members can’t vote, she says, that doesn’t mean they don’t play a role in getting resources to their areas.

“We think that being counted in the 2020 census is a foundational part of participating in democracy, and that’s what we’ve been sharing with families.”

“These are communities that have been politically disengaged or disenfranchised and undercounted in the census,” she said. “We think that being counted in the 2020 census is a foundational part of participating in democracy, and that’s what we’ve been sharing with families. We’re talking about millions of people nationally that risk being left out of the census.”

The efforts by groups like hers have been paying off. As it stands, the cities of Vista and San Marcos are ahead of their final self-response rate from 2010 by 5%. That means government census takers have less ground to cover.

But concerted efforts by organizers with deep connections to the community aren’t always so successful. In City Heights, a dense, immigrant-heavy neighborhood of San Diego, the census response rate is still lagging behind that of 2010.

Related: Census 2020 ads don't do enough to dispel immigrant fears, advocates say

An undercount would narrow the political power of Latinos in their own communities, says Rosa Olascoaga, a 24-year-old community organizer in City Heights, California.

“If our undocumented communities or our immigrant communities are scared to get counted, then we lose thousands and thousands of dollars every time we get counted, because the government doesn’t see us living here,” she said. “And that leaves us fighting for crumbs when we know we deserve more.”

She works for Mid-City Community Action Network and focuses on the transportation needs of local immigrants. In a car-centric city like San Diego, the census is one of the few ways to get funding for buses, trolleys and safer streets.

Ultimately, she knows the census — and this year’s election — must take a backseat to people’s immediate needs during the pandemic. Disillusionment with the government among Latino communities is high. And organizers like her can’t go door-to-door allaying people’s fears the way they did before the pandemic. Olascoaga hears those sentiments but hopes the community still prioritizes voting.

"I understand the government already made you feel that it doesn’t matter. These systems don’t work," she added, wishing that impactful, in-person activism were still possible in 2020. "It hurts that we can’t have those face-to-face interactions."

Time is running out for Latino communities — encompassing people who are undocumented, immigrants and US citizens — that have just a few weeks to make themselves count.

And a decade to live with the results.

This story is part of "Every 30 Seconds," a collaborative public media reporting project tracing the young Latino electorate leading up to the 2020 presidential election and beyond.

It’s March 31, 1992.

Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton and California Gov. Jerry Brown Jr. are both at Lehman College in the Bronx, New York, debating about education in urban America and sparring over tuition affordability — and gun control — just before the Democratic Party's presidential primaries.

Related: This young Afro Latino teacher and voter wants to be a model for his students

It’s pandemonium outside the college and all Nodia Mena can do is soak it in.

“I don't know anything about US politics, but it was such a huge enthusiasm,” she said. “Someone invited me to go around, we couldn't even get into the event. I mean, it was so many people, so many cars, and that was all new for me.”

This experience was Mena’s first introduction into American politics.

Mena is Afro Honduran and moved to the US nearly 30 years ago. She left Honduras when she was 19, but was able to vote for the first time before leaving.

She said the lack of change in her country led her to not take voting seriously.

“It was always whoever got into power will always do the same thing, they may have relied on corruption and so on. My very first vote was a rebellious vote. I voted for the least likely to win the party. I just felt like it didn't matter, like we didn't count. As a Garifuna, a Black woman in Latin America, my vote didn't matter.”

“It was always whoever got into power will always do the same thing, they may have relied on corruption and so on,” Mena said. “My very first vote was a rebellious vote. I voted for the least likely to win the party. I just felt like it didn't matter, like we didn't count. As a Garifuna, a Black woman in Latin America, my vote didn't matter.”

Related: How a trip to Honduras shaped one young US Afro Latino voter's identity

However, after seeing the enthusiasm toward politics in 1992, Mena started to take it more seriously and researched politicians and how the US government operates. The more she researched, the more interested she became.

In 2008, that feeling intensified.

Then the Democratic presidential candidate, Barack Obama, ran his campaign on the slogan, “Change we can believe in,” and the chant, “Yes, we can.”

“It wasn’t until Obama when I really started paying way more attention to what was going on,” she said. “The fact that he was there as a Black man, but his message, the way in which he connected with people, how generally he presented himself to people, it resonated with me personally.”

Mena canvassed for his campaign and made sure she connected with the people she spoke to, to encourage voter enthusiasm.

“I realized that we needed to, as Afro descendants, get involved with the decisions that are being made for us,” she said.

Her Afro Latina identity puts her in an interesting dynamic when candidates try to solicit her vote. Mena said candidates usually either go for the Black vote or the Latino vote, but never the Afro Latino vote. However, the fact that candidates don’t reach out to Afro Latinos isn’t an issue for her.

Related: This first-time Afro Latino voter is undecided. His biggest issue? Education.

“I don't think politicians should continue to think about people as ‘this is Indian,’ “this is Black,” ‘this is Latino,’” she said. “I think that this is the time where we should strive towards equity.”

“I don't think politicians should continue to think about people as ‘this is Indian,’ “this is Black,” ‘this is Latino,’” she said. “I think that this is the time where we should strive towards equity.”

As a Spanish-language instructor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Mena makes sure that she informs her students about Afro Latino history.

“In Latin America, that solidarity is nonexistent, as far as the non-Black Latinos with the Black Latinos. As a matter of fact, when you say Latinos, it does not include me in that group. You have to specifically say, 'Afro Latinos.' Why?”

These questions about Afro Latino solidarity with Latinos and African Americans are questions that she poses with her son, Brayan Guevara. The two of them, along with his other siblings, talk about everything, but especially race and politics.

“She'll always have MSNBC or something on and she's the type of person that always wants me to make up my own mind,” he said. “She never really told me, ‘Hey Brayan, you need to be a Democrat.’ She will always just try to ask me my opinions on things so I can be informed.”

Guevara is a sophomore at Guilford Technical Community College, where he is studying to become a teacher. He’s a first-time voter.

It took him a while to embrace his Afro Latino identity, but now that he has, he sees the importance of having teachers of color in the classroom, much like his mother.

“How teachers treat Black kids, which I have experienced in my time — it’s just the stigma that they already have for these kids,” Guevara said.

As Guevara and his mom navigate through this year’s election, he has no issue stating that Mena has been a big part of his political journey.

“She’s the only influencer I’ve ever had,” he said. “I don’t really look up to anybody else.”

This story is part of "Every 30 Seconds," a collaborative public media reporting project tracing the young Latino electorate leading up to the 2020 presidential election and beyond.

With a record 32 million Latinos eligible to vote this year, many political observers expected to see lots of Latino politicians and representatives at the virtual Democratic National Convention this year.

The convention aims to attract a diverse group of voters, with a speaker lineup that includes former First Lady Michelle Obama and former Ohio Republican Gov. Tom Kasich.

But Latino organizations argue the programming missed the mark. Though many national Latino leaders are taking part in daytime DNC panels, only three Latinas made the prime-time slots. They include New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who will only get 60 seconds to talk Tuesday night and New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and Nevada Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto.

“I am disappointed to see a lack of Latino leaders,” said Jess Morales Rocketto, executive director for Care in Action, a nonprofit advocacy group for domestic workers. Morales Rocketto is also a digital strategist who worked for the Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton campaigns.

The convention is the first time many voters tune in to the election and presents an opportunity to showcase what the Democratic Party can do for Latinos, she says. But with a lack of Latino representation, she adds, that might be a tough sell.

Morales Rocketto and others expected Julián Castro, the only Latino to run for president this election cycle, to have a more prominent role during the convention’s televised portion. He did take part in other virtual panels, briefly speaking at the Hispanic Caucus Meeting the first day of the convention. A Twitter hashtag #LetJulianSpeak trended the weekend before the convention’s start, signaling many Castro fans were unhappy.

“I’d be lying to you if I said I’m not disappointed that there aren’t more Latinos and Latinas generally speaking on that program, and that there’s not a Native American, not a Muslim American.”

“I’d be lying to you if I said I’m not disappointed that there aren’t more Latinos and Latinas generally speaking on that program, and that there’s not a Native American, not a Muslim American,” Castro said during an interview last week with MSNBC’s Alicia Menendez.

“If you think about the beautiful coalition that has become the Democratic Party over the last few years, I’m not sure it’s fully represented on that stage. But more important than the speaking, than the talking, is really the doing.”

Still, he says, he wants voters to focus on what presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden and his vice president pick, Kamala Harris, can do in a new administration.

Related: Trump, Biden boost efforts to reach Texas Latino voters

The question remains whether the campaign has done enough to tap into an increasingly young Latino voting bloc, many who had been fervent Bernie Sanders supporters.

According to the Pew Research Center, members of the growing cohort of US-born Latinos tend to be young, with a median age of 20.

Many, like 18-year-old Izcan Ordaz from Texas, are not staying up to watch the DNC. But they are paying attention.

“Personally, I haven’t been too involved with the Democratic Convention. I’m not planning on watching the entire thing, I’m just planning on watching some highlights from it,” Ordaz said.

Related: BLM protests are shaking up how this young Latino voter views US politics

However, Ordaz says he hopes for more debate on an economic stimulus package and solutions to issues with mail-in ballots.

Many have criticized the Biden campaign’s Latino outreach as too little, too late. Still, one thing the campaign has done to attract Latino voters, about one-third of whom tend to vote for Republican presidential candidates, is to enlist Republican strategist and CNN political commentator Ana Navarro to rally Biden voters in Florida. Navarro, who fled communism in Nicaragua, is not a fan of President Donald Trump.

That may dilute some of the Trump campaign’s messaging of Biden and other Democrats as communists and communist sympathizers.

But Morales Rocketto, like many Latino activists, says the Biden campaign still needs to prove itself.

To be Latino during an election season can feel like landing on a movie set of a suspenseful, high-stakes drama. It’s a story of contradictions. You are a star of the show — Latinos are projected to become the largest, nonwhite racial or ethnic electorate in 2020 — but it is usually set to a predictable, one-note soundtrack: “immigration, immigration, immigration.” An audience of pundits dissects the “Latino vote,” while advocates recite well-rehearsed lines: “Latinos are not a monolith. Ignoring the Latino vote will cost candidates at the polls.”

And perhaps the only reason the Latino vote narrative captivates political writers, pundits and especially candidates is because they want to know: “How does the story end?”

Related: Getting out the vote for the 2020 election: Lessons from Bernie Sanders' Latino outreach

Sure, action sequences turn on whether Democrats can rally Latinos or whether an incumbent president, whose political emblem is a border wall, has alienated Latinos who vote for Republicans. But it’s a story that comes down to the question: Will they show up on Election Day?

The answer depends, in part, on whether our stars feel like heroines on camera or specimens under a microscope, and whether they feel they are part of the US electorate or outsiders: “them,” “the other.”

“It matters a great deal, especially for those who are not politicized who have not developed an interest to engage or desire to engage with politics.”

“It matters a great deal, especially for those who are not politicized who have not developed an interest to engage or desire to engage with politics,” said Angela X. Ocampo, author of the forthcoming book, “Politics of Inclusion: A Sense of Belonging and Latino Political Participation.”

Before our stars became Latino voters, say researchers and voting rights advocates, daily experiences informed their enthusiasm for casting a ballot. To reach the ballot box, Latinos often must first traverse a battlefield of messages from the political left and right that casts Latinos as the perennial outsider. They will have shielded themselves from media coverage often portrays Latinos as rootless newcomers and asks that all-too-familiar question: “Where are you from?” Which presumes that the answer is: “Not here.” They will have faced a barrage of rejecting encounters, with nearly 38% of Latinos reported to the Pew Research Center in 2018 that they had been told to “go back,” chastised for speaking Spanish, or been on the receiving end of offensive slurs in the previous year. They will have pushed through the psychological impact of violent events, such as the 2019 mass shooting in El Paso, which was provoked by racist backlash against Latinos as a growing political force in Texas.

Related: The pandemic upended this Latino teen's senior year. Now it's upended his politics.

“After that terrible event, we were left at the mercy of a fear created for us,” writes Ilia Calderón, a national news anchor for Univision, in her new memoir, “My Time to Speak: Reclaiming Ancestry and Confronting Race.” The fear extended far beyond El Paso or Texas, beyond Mexicans and Mexican Americans, reaching Calderón, an Afro Latina thousands of miles away in Miami and but to Latinos across the country.

“We already had to deal with how the color of our skin makes some look at us a certain way when we walk into a store, what it means to be a woman walking around certain areas at certain times, but now we have to add our papers, last names, or nationality to the mix,” Calderón said.

From these experiences, “many Latinos in the U.S. learn that their standing in the U.S. social fabric is limited and below that of others,” writes researcher Ocampo, adding that it holds true for people whose roots run generations deep, or who arrived decades ago and raised their children.

A sense of belonging — meaning, how society perceives you — along with feeling respected and valued — can be powerful forces to mobilize or discourage voting. In his eulogy for the late civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis on July 30, former President Barack Obama said a central strategy to voter suppression is to convince people to “stop believing in your own power.”

Though Latinos possess a strong American identity, researchers have found Latinos register a lower sense of belonging than whites but slightly higher than Blacks. And given the nation’s racist hierarchy, Latinos, who can be of any race, with darker skin have a more tenuous sense of belonging than lighter-skinned Latinos. In 2018, the Pew Research Center found that following the election of Donald Trump, 49% of Latinos had “serious concerns” about the security of their place in the US. The implications can be significant. Ocampo found that a strong belief in belonging to US society can change the probability of voting by up to 10%, translating into tens of thousands of votes.

Demographics, though, seem to have little effect. Even in a state like Texas, where Latinos will soon become the largest demographic, they are underrepresented in nearly all areas of leadership. A forthcoming, statewide study by the Texas Organizing Project about Latinos’ relationship with the electoral system turned up a solid strain of unbelonging, particularly among working-class Latinos in urban areas.

“We are an ‘other.’ We still feel it,” said Crystal Zermeno, director of electoral strategy for the Texas Organizing Project.

That perception becomes a challenge when trying to convince eligible voters that the ballot box belongs to them.

“A lot of times working-class Latinos, they feel like voting is for other people. It’s not where they belong.”

“A lot of times working-class Latinos, they feel like voting is for other people. It’s not where they belong.”

Political campaigns may run on promises of better access to health care, tighter border security and help with college tuition. But to get the message across, candidates and parties need to make an authentic connection.

“I needed to make an emotional connection with an old, angry, white, Jewish man from Vermont [Sanders] with a demographic with an average age of 27, to say, ‘I understand your plight,’” said Chuck Rocha, a senior adviser during Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign effort to turn out Latino voters and recently released the book, “Tío Bernie: The Inside Story of How Bernie Sanders Brought Latinos into the Political Revolution.”

Sanders’ immigrant roots may have opened a door. But the connection comes from communicating, “You are part of our community and we’re part of your community,” Rocha said.

Related: Trump, Biden boost efforts to reach Texas Latino voters

Belonging, or at least the semblance of it, is a tool that Republicans use — including President Trump. With Trump’s “build that wall” chant; fixation on border security, and derogatory references to asylum-seekers and other migrants, Trump has drawn clear and powerful boundaries on belonging. Contained within his rhetoric, rallies and campaign videos is a choreography for performing American identity, patriotism and citizenship.

“Who do you like more, the country or the Hispanics?” Trump asked Steve Cortes, a supporter and Hispanic Advisory Council member, during a 2019 rally in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. During his 2020 State of the Union Address, Trump momentarily paused his typical vilification of asylum-seekers and other migrants to recognize one Latino: Raul Ortiz, the newly appointed deputy chief of the US Border Patrol — a servant of surveillance.

“He’s putting forth a clear version of what it means to belong and not to belong and who is a threat and not a threat,” said Geraldo Cadava, author of “The Hispanic Republicans: The shaping of An American Political Identity from Nixon to Trump.”

In the long term, Cadava says, Trump’s strategy is untenable because of the demographic direction of the nation. But in the immediate term, it is meant to rally his base and solidify support among voters in key states. Inviting Robert Unanue, CEO of Goya Foods, a major food brand favored by Latinos, to the White House in July, provoked backlash when the CEO praised the president. Still, for Latino Republican voters, it suggested that the White House is open to them.

This, combined with a weeklong, Hispanic outreach campaign that centered on promises to play up Latino business opportunities, in the eyes of Trump’s supporters, Cadava said, “he looks like a perfectly electable candidate.” It’s an image tailored for an existing base, which stands in contrast to the scene of Trump tossing rolls of paper towels to survivors of Hurricane Maria.

Overtures of belonging can also be seen in a move by Sen. John Cornyn, a Republican of Texas, who is up for reelection, to co-sponsor legislation to fund a National Museum of the American Latino. But advocates warn such messages ring hollow when matched with policies. Cornyn, a Trump supporter and lieutenant to Sen. Mitch McConnell, has aggressively backed repealing the Affordable Care Act even though his state has the highest uninsured rate in the nation — 60% of the uninsured are Latino. With news coverage of Latinos generally centered on border and immigration issues, and 30% of Latinos reported being contacted by a candidate or party, according to a poll by Latino Decisions, the lasting image is likely a photograph of a museum. This may explain why Cornyn is 10 points behind his Democratic challenger. To this, some say Democrats have failed to summon a vision of the nation that includes Latinos.

“We [Latinos] are part of the America, the problem is we haven’t made them part of the public policy and politics of our country because we don’t spend the time to reach out and make the connection to that community.”

“We [Latinos] are part of the America, the problem is we haven’t made them part of the public policy and politics of our country because we don’t spend the time to reach out and make the connection to that community,” said Rocha, who led a campaign by Sanders that scored record turnout among Latinos.

Related: This young Afro Latino teacher and voter wants to be a model for his students

Missing in American politics for Latinos is “a showman, somebody who stands up and who isn’t afraid of consequences to stand for our community the way [Trump] stands for racist rednecks. We haven’t seen that.”

Left is a roadmap of patriotism, of citizenship that positions Latinos in a neverending border checkpoint, not located in South Texas or Arizona, but built around the notion of an American.

“There are these tests being administered to see where these people are going to fit in the greater scheme of things if we have to deal with them,” said Antonio Arellano, acting executive director of Jolt Institute, a voter mobilization organization in Texas. “Patriotism can be displayed in many different ways, this administration has tainted nationalism by dipping it into the red cold racist filled paint that has been emblematic of America’s darkest moment in history.”

In a scathing opinion piece for The New York Times, Alejandra Gomez and Tomás Robles Jr., co-founders of Living United for Change in Arizona (LUCHA) accused political leaders of deserting Latino Arizonans, leaving them as scapegoats to a right-wing political agenda that was built on excluding and attacking immigrants and Latinos.

“The thing is, people want community. They want to belong to something that helps them make sense of the political world,” they wrote. “But they don’t trust politics or Democrats because both have failed them.”

While unbelonging may drive some people from the polls, it can also be a mobilizing force.

Following the 1990s’ anti-Latino and anti-immigrant campaign in California, that resulted in policies, such as denying education and housing to undocumented imigrants political groups harnessed the outrage and pain among Latinos in that state. In the 2000s, facing deportation, the young Latinos known as the “Dreamers” transformed their noncitizen status into a political asset and became a reckoning force across the nation. Millennials, in particular, reported to Ocampo their outsider status was a catalyzing force for political participation.

LUCHA and other advocacy groups have provided something candidates and parties have not: belonging. “We are reminding them and they are true leaders in our community, creating spaces to be themselves authentically in the world,” Gomez told me.

These advocacy groups have become a political force in Arizona, backing progressive candidates and galvanizing Latinos, not by stoking party loyalty but as “independent power organizations,” Gomez told me. In a state where Latinos are nearly a quarter of eligible voters, LUCHA and other groups helped roll back anti-immigrant laws and elected community leaders and Democrat Kyrsten Sinema to the US Senate by promoting a platform created not by a party, but by their community.

In late summer, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, Joe Biden, made belonging a central feature in “The Biden Agenda for the Latino Community.”

“President Trump’s assault on Latino dignity started on the very first day of his campaign. … Trump’s strategy is to sow division — to cast out Latinos as being less than fully American.”

“President Trump’s assault on Latino dignity started on the very first day of his campaign. … Trump’s strategy is to sow division — to cast out Latinos as being less than fully American,” it says.

Biden’s agenda includes a host of policy offerings including a public option for health care, immigration reform and addressing climate change. It remains to be seen if that’s enough, if the strategy will amount to policies wrapped up in an anti-Trump message. And this brings to mind a critical point that Rocha made about appealing to Latino voters: Latinos changed Sanders himself, by courting them he gained a more complete portrait of the nation. Belonging, after all, is reciprocal.

Come Election Day, whether someone coming off a double shift or mourning family members who died in a pandemic, or a student facing down a deadline for a paper will take a few hours — Latinos stand in lines that are twice as long as whites — a ballot cast will be the end result of a long journey, an epic drama that began long before a campaign season.

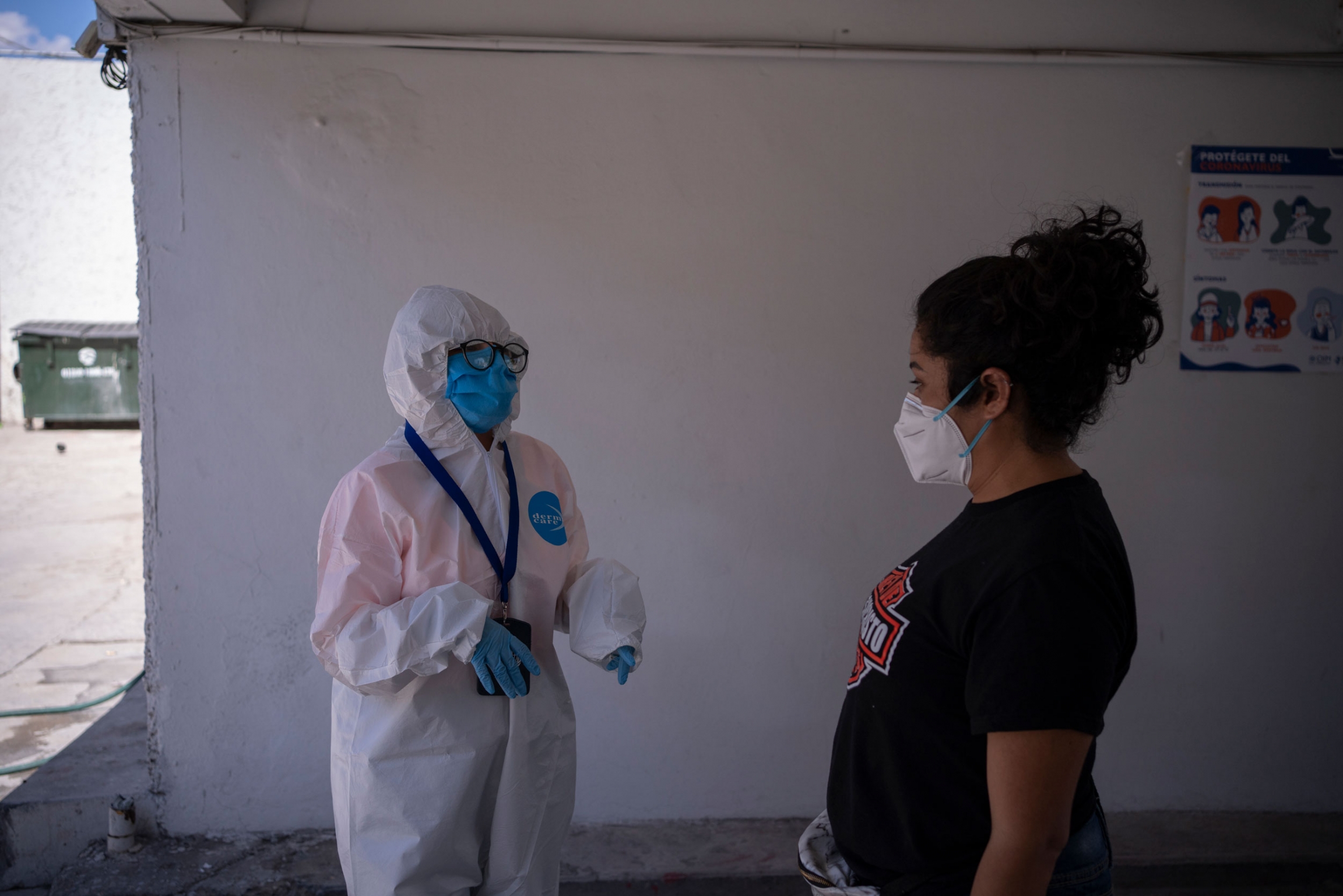

Ernestina Mejía knew people were getting sick all around her this spring. She heard co-workers coughing in the bathroom at work. Others whispered about colleagues looking feverish.

Mejía wasn’t surprised. She works at Primex Farms, a dried fruit and nut producer based in Wasco, California, about 130 miles north of Los Angeles. Mejía, who moved to the US from Mexico a decade ago, sorted pistachios indoors on an assembly line, working in close proximity to others. Primex offered them no masks, no gloves and no protection against the coronavirus, she said.

Then, in mid-June, Mejía fell ill.

“I started feeling shivers and a terrible cough that wouldn’t let me sleep,” she said in Spanish.

Mejía, along with her husband and youngest daughter, had contracted the virus. So did 99 of Mejia’s coworkers, or about a quarter of Primex’s 400-person workforce, according to a tally by the United Farm Workers, a farmworkers’ union. One of her Primex colleagues, Maria Hortencia Lopez, 57, died on July 13 from COVID-19, according to friends and the UFW. Meanwhile, Mejía said, Primex did not acknowledge that people were falling ill.

Horrified at the outbreak, Mejía and other Primex employees took part in a one-day strike in late June to protest what they viewed as their employer’s failure to protect them. They also demanded an investigation by the state’s attorney general.

Their situation highlights the tightrope farmworkers must walk to protect their health and jobs while avoiding retaliation from their employers. Within weeks, at least 40 Primex workers, many of whom were active in the strike, were terminated, former workers told The World. Others said they feared the same fate if they spoke up.

From the start of the pandemic, warnings were clear that farmworkers — deemed “essential” to the nation’s food supply and thus exempt from lockdown orders — would be at high risk for COVID-19. Across the US, an estimated 2.5 million farmworkers often work in cramped spaces, carpool to work and live in crowded homes. Many are immigrants and refugees. They’re part of an industry where safety and labor standards are notoriously weak, but many workers cannot leave their jobs because they’ll fall into poverty. The stakes are even higher for undocumented workers, whose legal status leaves them vulnerable to immigration enforcement.

Related: Farmworkers are now deemed essential. But are they protected?

Now, those early warnings are bearing out as outbreaks are reported at farms and food processing plants across the US. In July, dozens of farmworkers at a dorm-style housing facility in Southern California tested positive for the coronavirus. In southwest Florida, Doctors Without Borders has noted high rates of infections among farmworker communities and is providing them with COVID-19 testing and virtual medical consultations.

Employers’ lack of disclosure to employees about workplace infections is not unusual. Jesse Rojas, a business consultant Primex hired to speak to the media on its behalf, told The World the company has been following official safety guidelines and has been “very proactive in communicating with employees.”

In a statement to the local ABC television station, the company attempted to distance itself from the possibility that its workers were infected on-site.

“Primex cannot control the circumstances or monitor what employees are doing outside on their own time,” it said. “Primex is known as one of the cleanest plants in the industry.”

Mejía, along with several current and former Primex workers, also said that the farm did not provide masks for several months as the coronavirus surged across the country. When it did, cloth masks were provided for sale on-site for $8 each.

“That’s not something we can afford,” said Mejía, who earns $13 per hour. In the end, she said she purchased handmade masks from a co-worker for $4 apiece.

Primex denies selling masks to employees.

“The company has never charged employees a dime for a face mask.”

“The company has never charged employees a dime for a face mask,” Rojas said.

Since the strike, Mejía, who is now back at work, said conditions at the processing plant have improved somewhat. For instance, employees’ work breaks are now staggered to avoid crowding. Masks and gloves are available for free.

“Things are better,” she said. “I just hope that they stay like that once the spotlight moves away.”

Yet, Mejia still hears people coughing at work. She knows her co-workers worry about missing a paycheck or losing their jobs. Many immigrant workers are blocked from unemployment insurance and have been left out of federal relief bills for the coronavirus.

Related: California hospital translates coronavirus information for immigrants

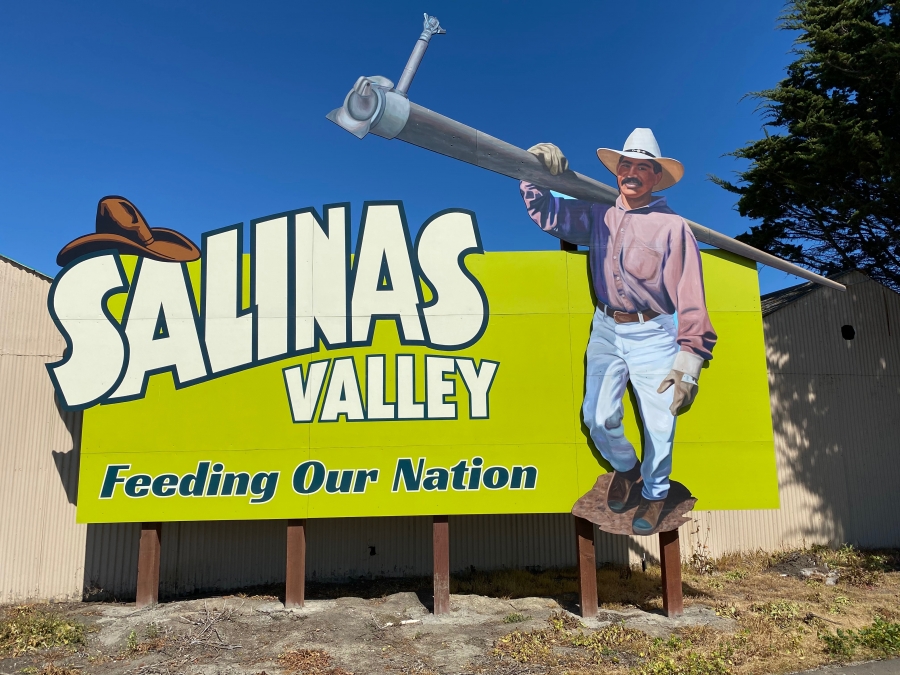

Some US lawmakers are pushing for broader federal help — and more safety at farms. Rep. Jimmy Panetta, a Democrat of California whose district includes the heavily agricultural Salinas Valley, has co-sponsored bills that aim to loosen eligibility requirements so that workers, regardless of their immigration status, have access to financial aid during the pandemic. But those initiatives have not succeeded at the federal level. Panetta and others are pushing to reimburse farms for personal protective equipment, or PPE.

“We're basically doing our job and making sure that the funding is there so that they can have this PPE,” Panetta said. “You want to make sure that these producers are requiring that their employees wear the PPE.”

There are still no national mandates to protect workers — only nonbinding guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. That’s a problem, said Armando Elenes of United Farm Workers, which supports the workers at Primex.

“They’re recommendations, not requirements,” Elenes said. “That makes it difficult to enforce because they have no teeth.”

Related: US seafood workers fight unsafe conditions amid pandemic

Meanwhile, workers have paid a high price on farms that have been slow to protect them.

Another farmworker, Anastacio Cruz, who harvested white button mushrooms at a farm south of San Francisco for about 13 years, contracted the coronavirus this spring. California declared its shelter-in-place order in mid-March. But Cruz, who spoke to The World in Spanish, said he continued to work indoors without a mask and did not worry about the risks.

“You just think that nothing is going to happen, right?” said Cruz, who migrated to the US from Oaxaca, Mexico.

Anastacio Cruz, center, a farmworker, leaves Natividad Medical Center in Salinas, California, where he spent more than six weeks after contracting the coronavirus, on June 29, 2020.

Courtesy of Natividad Medical Center

Then, his body started aching. In April, he was hospitalized at the Natividad Medical Center in Salinas for 13 weeks. His youngest daughter, Isela, sat next to Cruz.

“It was a very hard situation and very slow progress,” she said. “He was, like, six weeks in a coma.”

His hospital stay included 50 days on a ventilator, during which Isela enrolled him in Medicaid. Cruz is now recuperating at home. During an interview over Zoom, he pointed to the small tubes pushing oxygen through his nose.

“I’m not sure when I will work again. I’m telling people to take care of themselves, wear the mask, so that people don’t go through this. It’s hell for the family.”

“I’m not sure when I will work again,” he said. “I’m telling people to take care of themselves, wear the mask, so that people don’t go through this. It’s hell for the family.”

Cruz did not want to name the mushroom farm where he worked, concerned it could hurt his chances of returning to his job. Though Cruz was laid off with two weeks’ pay, he said his employer told him he could come back.

Speaking up can be risky, as María Irma Escobedo knows all too well. After working for nearly two years sorting pistachios at Primex Farms, she was one of at least 40 workers whose jobs, facilitated through a staffing agency, were terminated. Many of those terminated were active in the workers’ strike and said they received no warning they would be let go.

“I know this was retaliation against us,” Escobedo said. “Now, we’re out of work. My only source of income. And this was my fear from that start, that this would happen for speaking out.”

The United Farm Workers said it will file charges with the National Labor Relations Board alleging Primex failed to protect them and illegally retaliated against them for protesting.

Rojas, speaking on behalf of Primex, told The World the staffing cuts are based on usual seasonal reductions. He did not answer questions about year-to-year comparisons or allegations by Primex workers and the UFW that new people are being hired to work at the plant, sourced by another staffing agency, to replace the workers recently let go.

Escobedo said that she will continue to fight back, albeit from home.

In June, she tested positive for COVID-19 and was hospitalized for three days, she said. She is still recovering.

Jonathan, an asylum-seeker from Haiti, has a collection of bus tickets from his trip last fall from Florida to the US-Canada border. The last bus dropped him off in Plattsburgh, New York, a little over 20 miles from Canada. Then, he took a taxi to the border.

But he didn’t go to an official border crossing. Instead, he followed instructions from other asylum-seekers.

“My friend sent me every [piece of] information,” said Jonathan, who asked to use only his first name because his asylum case is pending.

That information included videos posted online of an informal crossing point north of Plattsburgh. The spot, a country road that reaches a dead end in a gravel patch at the border, has become so popular with asylum-seekers that police now wait, 24/7, on the Canadian side to detain new arrivals.

But like tens of thousands of other asylum-seekers trying to reach Canada from the US in the past four years, Jonathan took this route to avoid a bilateral deal between the two countries known as the Safe Third Country Agreement. Signed in the wake of 9/11, the deal allows both the US and Canada to turn back asylum-seekers who present themselves at official border crossings if they first passed through the other country. In practice, it has more frequently impacted asylum-seekers arriving in Canada after having lived in or transited through the United States.

But last week, a Canadian judge ruled the agreement violates asylum-seekers’ rights because of what happens after people are turned back to the US if they arrive at official border crossings. Detention conditions to which returned asylum-seekers may be subject in the US violates asylum-seekers’ protections under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the judge found.

Related: Canadian court weighs whether the US is safe for asylum-seekers

Alex Neve, secretary general of Amnesty International Canada, which was a party to the legal challenge, explained that those who do arrive at the US border at official crossing points and are turned back are returned to US border agents.

“You may very well end up in detention for an extended period of time. In immigration detention centers, sometimes commingled with criminal convicts. That’s very commonplace.”

“You may very well end up in detention for an extended period of time. In immigration detention centers, sometimes commingled with criminal convicts. That’s very commonplace,” Neve said.

In her ruling Wednesday, Canadian Federal Court Justice Ann Marie McDonald focused on the experience of plaintiff Nedira Mustefa, an asylum-seeker who is originally from Ethiopia.

After being turned back from Canada, Mustefa spent a month in a New York county jail, which included time in solitary confinement until she was released on bond. Unable to get halal food in jail, Mustefa lost 15 pounds.

McDonald wrote: “Although the US system has been subject to much debate and criticism, a comparison of the two systems is not the role of this Court, nor is it the role of this Court to pass judgment on the US asylum system.”

However, she continued: “Canada cannot turn a blind eye to the consequences that befell Ms. Mustefa in its efforts to adhere to the [Safe Third Country Agreement].”

The ruling leaves the agreement in place for the next six months to allow the government to respond. Amnesty International Canada and the Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers have urged Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's government not to appeal.